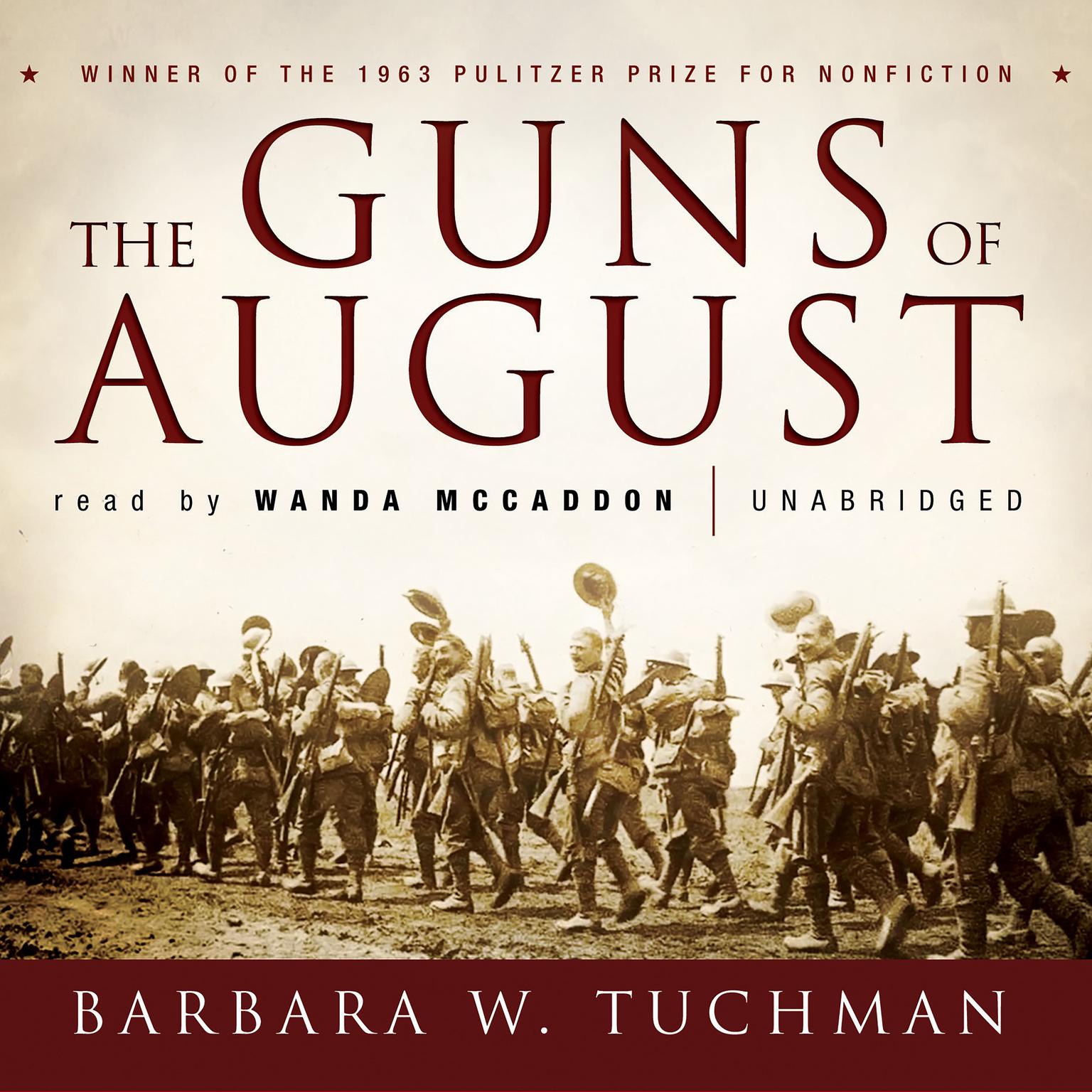

Publisher Description

In this Pulitzer Prize–winning classic, historian Barbara Tuchman brings to life the people and events that led up to World War I.

This was the last gasp of the Gilded Age, of kings and kaisers and czars, of pointed or plumed hats, colored uniforms, and all the pomp and romance that went along with war. How quickly it all changed—and how horrible it became.

Tuchman masterfully portrays this transition from the nineteenth to the twentieth century, focusing on the turning point in the year 1914, the month leading up to the war, and the first month of the war. With fine attention to detail, she reveals how and why the war started and why it could have been stopped but wasn’t, managing to make the story utterly suspenseful even when we already know the outcome.

A classic historical survey of a time and a people we all need to know more about, The Guns of August will not be forgotten.

Download and start listening now!

“There is so much in this book…there is always so much in any book about military history–names of officers, names of soldiers, names of battles, names of places, etc.–that a re-reading is almost necessary if one is to remember anything other than the basic facts presented in the book. Military histories are, to me, always a bittersweet experience: whatever fascinating facts, speculations or even gossip are included, there is always the underlying idea that people, in this case numbering in the millions, were dying as the story unfolded. They are as anonymous in death as they were in life. “Their position was overrun”, “the battalion was routed”, and “victory was complete” are basically code words for the basic idea that many people died, away from their home and their loved ones and to be buried, if at all, in an unmarked grave. Napoleon single-handedly managed to decimate the French male population during the first fifteen years of the nineteenth century through his continuous years of war, over 1.5 million young French men never returning home. What makes this book even more depressing than most of its type is that we know that what happens in August of 1914 is nothing more than a murderous prelude to an even more murderous four years of what has been called “competitive homicide”. And yet, in the same way that we find it difficult to drive by an automobile accident without slowing down to see what happened, so, too, do we read about these terrible wars and the horrific tolls they exacted on both those who died and those who did not. Tuchman, as has been noted by hordes of readers and reviewers much more insightful than me, manages to bring to light enough human foibles among the leaders and humanity among the soldiers to make it not only readable but, dare I say, enjoyable. She even does the impossible…presenting in a cogent manner the actual reasons, other than the assassination of the Archduke Ferdinand, why the First World War came about and, indeed, makes it seem unavoidable to the nations involved as they roused themselves from, as someone noted, “the boredom of peace”. It has been said that “…armies always prepare to fight the last war”, meaning that they know what worked before and use that as the guide in preparing for the next war. Tuchman shows us that some of the French and Russian generals seemed to be preparing to fight the war before the last war, still relying on cavalries to somehow survive machine-gun fire and bayonets to overcome artillery bombardment. The only heroes in this story seem to be the Belgians, and especially Albert, their king, and the Russian soldiers who were expected to die in great numbers and duly obliged. (And even the Belgians come out brave but very naive, refusing to compromise their neutrality by asking for assistance until it has become overrun by the Germans.) Tuchman does one other thing: she does away with the idea that the populations of the nations involved were unwillingly lead by the nose into war by their leaders. As she says about workers on the street, they may have considered themselves socialists, but when war was declared, their allegiance switched “from Marx to Mars”, the god of war. “It is a joy to be alive!” screamed a headline in one Berlin newspaper as Germany declared war on France. Of course, this is because they all thought the war would be short–the Kaiser promised his troops in August that they would be back home “before the leaves fall”–and they all thought their side would win. This naivete was only matched by those who thought the nations of Europe had their economies so enmeshed with each other that a war was impossible. The only thing more depressing for the reader than the litany of mistakes, misinformation and treachery is the idea that when the book is ended, the war has only begun. As dreadful as the tale already told has been, what is to follow will be immeasurably worse.

.”—

Dennis (5 out of 5 stars)